Authors

| Saju Palayur Senior Technical Director of Software Engineering |

Iñaki Val Beitia Principal Standards Engineer |

Sigurd Schelstraete Senior Technical Director of Standards Engineering |

Introduction

Quality of Service (QoS) is a set of protocols and techniques to prioritize specific data services within a network to improve KPIs such as latency, jitter, and reliability, thereby improving user experience. Each of these data services has a specific set of QoS requirements. In the early days of Wi-Fi, the technology functioned on a "best-effort" basis, ensuring fairness in accessing the wireless medium without differentiating traffic based on e.g., priorities. However, this model proved inadequate as applications requiring real-time data transmission with time bounded latency, such as voice and video streaming, became increasingly common. To overcome these challenges, various QoS mechanisms have been introduced into the Wi-Fi standard. They enhance network performance by employing strategies like traffic prioritization, bandwidth allocation, and congestion management, offering a more satisfactory user experience.

Quality of Service (QoS) is a set of protocols and techniques to prioritize specific data services within a network to improve KPIs such as latency, jitter, and reliability, thereby improving user experience. Each of these data services has a specific set of QoS requirements. In the early days of Wi-Fi, the technology functioned on a "best-effort" basis, ensuring fairness in accessing the wireless medium without differentiating traffic based on e.g., priorities. However, this model proved inadequate as applications requiring real-time data transmission with time bounded latency, such as voice and video streaming, became increasingly common. To overcome these challenges, various QoS mechanisms have been introduced into the Wi-Fi standard. They enhance network performance by employing strategies like traffic prioritization, bandwidth allocation, and congestion management, offering a more satisfactory user experience.

Throughput is another critical parameter for evaluating network efficiency, which quantifies the amount of data transferred over the network over time. Various factors, including wireless signal strength, interference levels and competing network traffic, can affect throughput and other KPIs. While throughput measures the data transmission capacity of the network, QoS works to fine-tune high-priority services and applications. Throughput and QoS are both essential for network performance.

In Overlapping Basic Service Sets (OBSS) scenarios, several BSSs (i.e., “networks”) use the same primary channel. In this case, bandwidth becomes a shared resource and diminishes the resources available to each BSS individually. This setup poses distinct challenges in upholding the required QoS levels in each BSS, without degrading the other BSSs. While current mechanisms may be adequate at regulating QoS within its own BSS, it may overlook the traffic conditions in the OBSS. As a result, if each BSS maximizes its traffic without accounting for the OBSS sharing the wireless resources, can lead to system-wide complications.

Over the years, successive generations of Wi-Fi standards have typically raised the bar on throughput, but they have also added crucial features intended to facilitate QoS. In this paper, we’ll provide an overview of these QoS-related Wi-Fi features and offer insights into potential areas for future improvements.

History of QoS features in Wi-Fi

Early Wi-Fi standards

The initial Wi-Fi standards were published in 1997 and 1999. One of the fundamental decisions was how to regulate access of multiple devices to a shared medium. To this end, Wi-Fi adopted CSMA/CA (“Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance”) as the basic mechanism.

Wi-Fi's early days started with two fundamental functions for channel access: the Distributed Coordination Function (DCF) and the Point Coordination Function (PCF).

- DCF (Distributed Coordination Function) implements the CSMA/CA access method. It checks the radio link for any activity before sending ("Carrier Sensing”). When the link is found to be idle, devices will wait for a random delay (“backoff”) before transmitting. During this delay, the medium continues to be monitored and transmission is suspended if any activity is detected before the end of the backoff. This random delay reduces the probability of collisions ("Collision Avoidance”).

- PCF (Point Coordination Function) provides a contention-free access method controlled by a central controller block (Point Coordinator or PC), typically an access point. The PC has higher priority to the medium and can reserve the medium to essentially create contention free periods. Within those periods it can direct (“poll”) specific devices to transmit. After the contention-free access time window finishes, medium access reverts to DCF. This procedure is repeated cyclically.

DCF ensured fairness for contention; however, it lacked the specialized features necessary for QoS management. This meant it couldn't differentiate between various types of data traffic, such as real-time video or latency-sensitive voice applications, which led to limitations in delivering a consistent and reliable user experience.

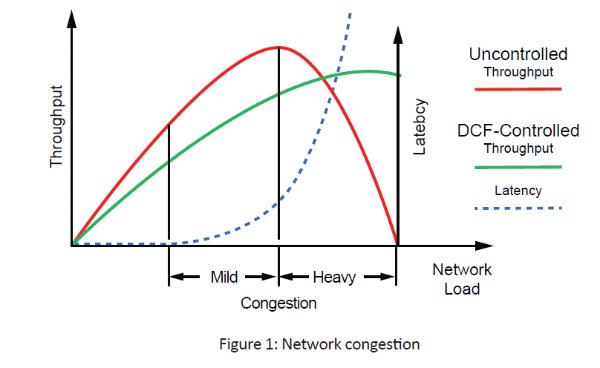

Another important problem related to DCF is that its throughput performance drops under high congestion scenarios, which also affects the rest of the KPIs. Figure 1 illustrates the behavior of network throughput as a function of the network load (essentially, the number of contending devices). It shows two different curves under two congestion regions. The left side means no congestion; the network's aggregated throughput increases with the number of devices until it reaches the capacity limit of the network, and we are under congestion conditions. Depending on the approach, the behavior on the right side of the figure will be different. In addition to the throughput decrease, the latency KPI increases, making it difficult to meet QoS requirements.

PCF provided a PC-directed way of selectively allowing certain devices to the medium, providing the basis of QoS. However, PCF is rarely used and has been deprecated in later versions of the Wi-Fi standard.

Recognizing these limitations, appropriate additions to the Wi-Fi standard became necessary. Later amendments to the standard aimed to address the deficiencies of DCF and PCF, introducing new protocols and mechanisms to prioritize and manage different types of traffic more efficiently. This transformation ultimately resulted in a significantly enhanced Wi-Fi experience, especially for applications demanding QoS guarantees.

IEEE 802.11e

Understanding the need for native QoS support within Wi-Fi, the 802.11 standards group commenced work on a new amendment 802.11e ("Medium Access Control (MAC) Quality of Service Enhancements”). This amendment was finalized and published in 2005. Note that some of these featured were adopted by the Wi-Fi Alliance (WFA) through its Wi-Fi Multimedia (WMM) program (see later).

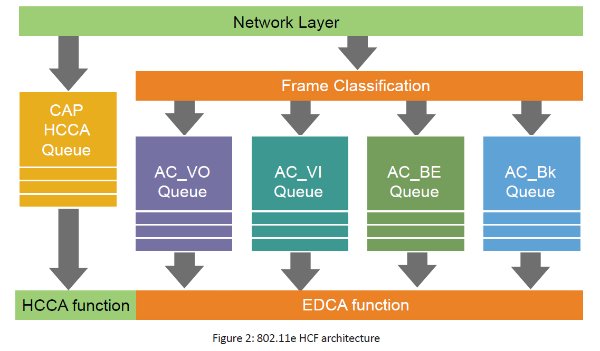

The best features of DCF and PCF were combined to create the Hybrid Coordination Function (HCF). HCF introduced new QoS features like Enhanced Distributed Channel Access (EDCA) and HCF Controlled Channel Access (HCCA), also adding support to Traffic Specification (TSPEC) for the management of QoS traffic requirements.

EDCA (Enhanced Distributed Channel Access) categorizes traffic into Access Categories (ACs) to obtain different priority classifications. Each AC has its own message queue and specific contention parameters (AIFS & CW) for accessing the wireless medium. For instance, voice might be given the highest priority, while background data traffic might be given the lowest. EDCA ensures critical data, like voice and video, can get prioritized access in Wi-Fi networks over other types of traffic (Best effort and Background).

802.11e also allows the device that gains access to the medium to maintain control for more than a single transmission in a so-called Transmit Opportunity (TXOP). With TXOP, a station can send multiple frames without being interrupted by other stations trying to use the channel.

HCCA (HCF Controlled Channel Access) is a polled access mechanism where a Hybrid Coordinator (HC) schedules contention free period TXOPs for the STAs, within a Controlled Access Phase (CAP), which can be repeated along the Beacon periods. HCCA is different because it uses a central scheduler to decide when stations can use the channel, allowing to guarantee QoS for high priority services (Voice and Video ACs). The AP ensures the access to the wireless medium by contending for the channel with more aggressive contention parameters. Contention Access Periods (CAPs) are allocated as necessary, with the remaining time utilized by Enhanced Distributed Channel Access (EDCA).

TSPEC (Traffic Specification) defines the QoS requirements of a data flow or Traffic Stream (TS), detailing attributes such as data rate, delay limits, and traffic nature. The stations (STAs) may request the Access Point (AP) for the admission of such TS for some specific QoS requirements, assigned to a Traffic Stream Identifier (TSID). The AP may deny by means of admission control, which guards against network overload, preserving the set QoS standards crucial for VoIP and video streaming applications. Ethernet frames can carry an optional higher layer 802.1Q tag called DSCP (Differentiated Services Code Point) for traffic priority. By means of the TCLAS (Traffic Classification) parameter set, it is possible to identify such frames belonging to a particular TS, and hence to the corresponding AC. However, there is no direct map between DSCP and the ACs.

Figure 2 depicts how EDCA and HCCA interact, showing the queues architecture for each of the ACs. By means of TSPEC requests, the STAs may reserve resources for their traffic streams. Each of these streams are classified and enqueued, depending on the access method used. EDCA has four queues, while HCCA may use one queue for managing its own TSPEC configurations.

IEEE 802.11n, 802.11ac

802.11e remained the corner stone for QoS in Wi-Fi. Later amendments like 802.11n and 802.11ac focused on enhancing throughput over QoS features. The spectacular throughput enhancements of 802.11n (from 54 Mbps to 450 Mbps maximum PHY rate) were provided by some innovative PHY and MAC features. For instance:

- MIMO uses multiple antennas to achieve higher data rates.

- Frame aggregation enabled sending multiple MAC frames in a single transmission, minimizing MAC overhead.

Additionally, 802.11ac extends the channel bandwidth to as much as 160 MHz. 802.11ac also introduced Multi-user MIMO (MU-MIMO), which facilitates concurrent communication with several devices.

Although not primarily engineered for QoS, providing increased throughput increases resources for the network and thereby indirectly reduces network latency and congestion.

IEEE 802.11aa

This amendment (officially named “MAC Enhancements for Robust Audio Video Streaming”) was based on the work done in 802.11e and focused on enhancing audio and video transport over

wireless networks to better support video streaming applications.

802.11aa introduced several mechanisms related to improvement of the QoS, such as:

- SCS (Stream Classification Service) allows a STA to explicitly request downlink resources to the AP for meeting QoS requirements for applying to specific traffic flows. One of the main differences with the TSPEC feature is that SCS applies QoS rules to a Traffic Identifier (TID) or 802.1Q User Priority (UP), making it more generic that TSPEC. After classification, these data frames are allocated to an access category and tagged for drop eligibility. Drop eligibility indicates whether a traffic flow can be discarded if it runs out of buffer space or bandwidth.

- OBSS Management mechanisms were introduced, divided into different features.

- Additional Qload metrics were defined, which try to quantify each BSS load, classified in different types of network traffic. These metrics are exchanged between the OBSS APs, to ensure that the requested new traffic will not interfere with current admitted traffic.

- HCCA enhancements for coordinating two or more AP HCs by means of exchanging between the APs their time scheduled CAP information. This time coordination allows to avoid collisions between the CAPs of each BSS, solving one of the major HCCA problems.

Like 802.11e, 802.11aa tried to enhance the QoS related features and overcome some of the drawbacks found in the previous QoS standard, including HCCA. Still, HCCA has not found widespread application even with these enhancements

IEEE 802.11-2016

The 2016 release of the 802.11 standard extended to SCS concept introduced in 802.11aa.

MSCS (Mirrored stream classification service) enables a client device to request the AP to apply specific QoS requirements of downlink data flows using QoS mirroring. It means that instead of requesting explicitly as in the case of SCS feature, MSCS monitors the corresponding uplink flows sent by the STA, and the AP derives QoS rules for downlink flows. MCSC does not replace SCS, both are complementary and designed to be used independently or together.

IEEE 802.11ax, be

802.11ax and 802.11be provided the next generation of Wi-Fi after 802.11ac by adding new features such as OFDMA, Multi-Link Operation (MLO), 1024-QAM, 4096 QAM, and BSS Coloring. With these amendments, the focus on QoS was less immediate, but the enhanced throughput and resource flexibility provided by 802.11ax and 802.11be indirectly provide new mechanisms

to enhance QoS.

- OFDMA allows multiple users to share a single channel by dividing it into smaller sub-channels. This boosts efficiency, reduces latency, and improves throughput.

- 1024-QAM is a modulation scheme that encodes 10 bits per symbol, allowing for higher data rates. It’s used in Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 7 for greater throughput but requires a higher signal-to-noise ratio.

- 4096 QAM is a modulation scheme that encodes 12 bits of data per symbol, allowing for high data throughput. However, it’s more sensitive to noise and requires favorable channel conditions.

- MLO (Multi-Link Operation) allows a station to establish multiple links in multiple bands with one or more access points for improved reliability, throughput, and latency.

- BSS Coloring labels frame headers from an access point with numerical “colors” for easy network identification by client devices. This minimizes co-channel interference and enhances network performance.

- SCS Enhancement: 802.11be introduced the QoS characteristics element to SCS and restricted TWT procedures, enabling the possibility of requesting QoS resources for traffic flows in downlink, uplink, and peer-to-peer directions.

One important innovation in 802.11ax was the introduction of Triggered Uplink Access (TUA) as a channel access mechanism. TUA is somewhat reminiscent of the PCF mechanism. TUA enhances uplink performance by enabling client devices to send data upon receiving a "trigger" frame from the access point. This synchronized approach cuts down on waiting periods and contention, thus lowering latency. It also fine-tunes the use of the uplink channel among multiple devices, boosting overall network efficiency since fewer devices need to contend for the medium. This effectively shifts network access toward a more scheduled approach controlled by the access point. Setting MU EDCA parameters allow the AP to control the extent to which client devices will use contention as opposed to TUA.

Summary

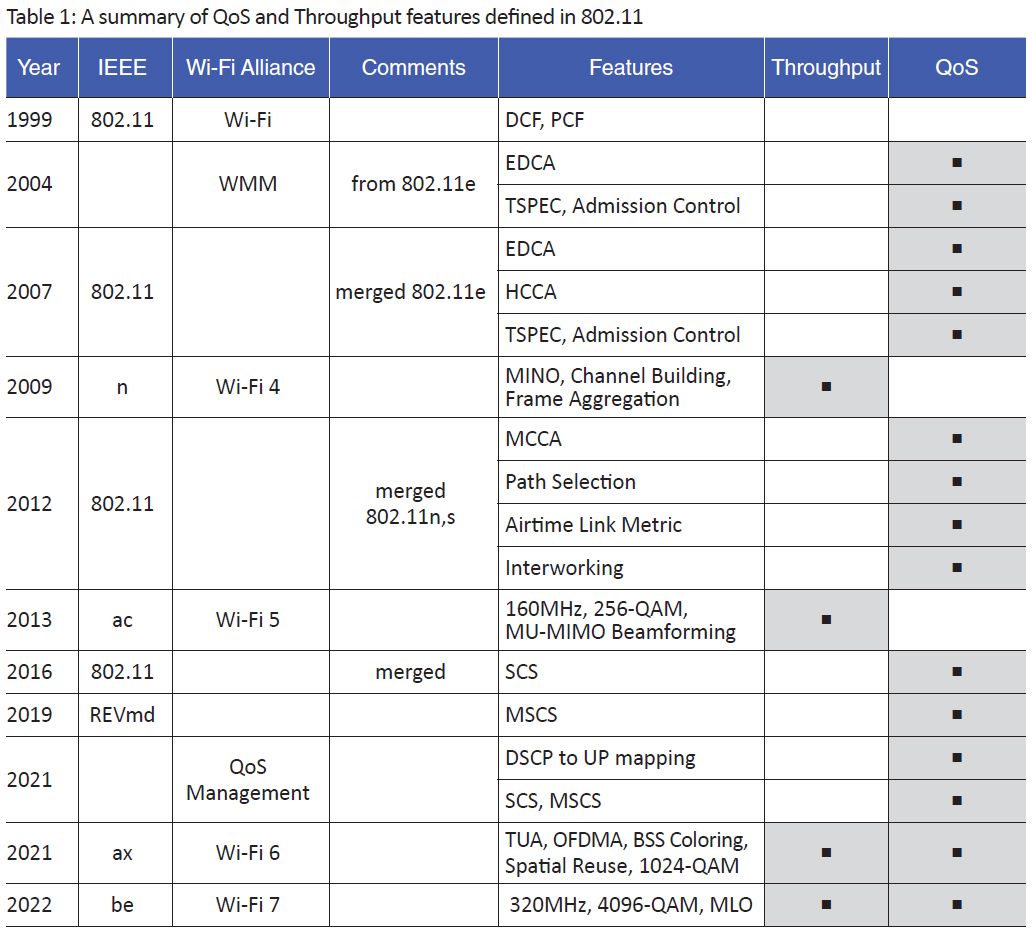

A table of Throughput and QoS enhancements features in the standards is shown below in Table 1.

Wi-Fi Alliance

The 802.11 standards body defines technical specifications for the successive Wi-Fi generations. The Wi-Fi Alliance (WFA) builds upon these standards to define industry programs that bundle some of the more salient features into comprehensive test and certification programs, occasionally even adding features in addition to what is defined in 802.11. Several WFA programs are specifically focused on QoS.

For instance, WFA’s Wi-Fi Multimedia (WMM) program, is based on a subset of the IEEE 802.11e standard, adopting EDCA, TXOP and TSPEC features. As in the IEEE standard, WMM classifies traffic into the same four access categories, defining how to map directly into the predefined 802.1Q user priorities.

Building on WMM, the WFA's Wi-Fi CERTIFIED QoS Management™ specification harmonizes QoS treatments between wired and Wi-Fi networks, allowing devices to assign specific application IP flows to WMM-defined categories. This can be done by means of the direct mapping between the DSCP tags and user priorities (DSCP-to-AC mechanism), and therefore with the Wi-Fi access categories. Additionally, it adopted SCS and MSCS mechanisms for QoS management, which helped to address some of the evolving user needs for consistent QoS in Wi-Fi environments.

Conclusions

Wi-Fi standards have evolved to meet the growing demands of modern applications. One of the crucial threads of this progression is the need for improved Quality of Service (QoS). Over the years, Wi-Fi has provided native features to enhance QoS in various ways.

The diversity of applications like IoT devices, augmented reality, telemedicine, real-time gaming, and ultra-high-definition streaming has evolved. The complexity of scenarios often includes congested networks with repeaters. These applications have varying traffic requirements; some need high bandwidth, and others require guaranteed latency.

Current QoS mechanisms all work in combination with a contention-based protocol (DCF). While contention-based mechanisms can address many needs, they may fail to ensure timely data delivery for critical applications in increasingly congested environments. As the number of Wi-Fi devices continues to grow and congestion becomes more likely, it may be necessary to consider other forms of network access that rely more on central scheduling, as HCCA has attempted to do in the past.

While HCCA did not take off in the market, some form of Hybrid Coordinator (HC), collocated within the Access Point, could be revamped to incorporate the need for time-sensitive wireless tools. The network can prioritize resources by introducing scheduled access alongside contention-based mechanisms. This scheduled access can reserve transmission opportunities (TXOPs) for high-priority tasks, ensuring that time-sensitive data is not at the mercy of network congestion. Such a new network access mechanism would also have to be robust in the presence of OBSS and be defined in a way that allows coexistence with legacy devices.

Efficient use of the wireless spectrum is not just about maximizing throughput but also about ensuring the timely and reliable delivery of packets. Applications demanding high QoS, like VoIP calls, video streaming, or online gaming can improve, even in a congested environment. It could guarantee end-users a superior and consistent experience. As emerging technologies push the boundaries of what's possible in wireless networks, a robust QoS mechanism ensures that the next Wi-Fi standard can handle future innovations.